The Cowboy/Gypsy Boot: The Wide Image as Method for Humanist Inquiry and Action

Sting: The case of Timothy Dean and Gemmel Moore

Shortly after 1:00 a.m. on January 7, emergency responders arrived at a second-floor apartment in West Hollywood. Entering the home, they found a 55-year old man lying on a mattress in the living room. He was unresponsive and declared dead at 1:36 a.m. (Haag 2019).

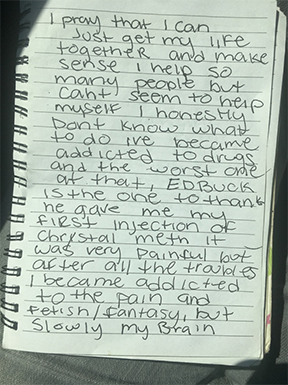

Gemmel Moore's journal,

this was discovered after his death

There was much to go over at the scene: sex toys and drug paraphernalia littered the room. There was a basket of fresh, clean white underwear to the side of the mattress, a rumored fetish of the homeowner. Mirrors plaster the walls. In the living room alone there were three large mirrors installed at varying angles, which the homeowner reportedly used to keep watch of his guests (Cannick 2018).

Timothy Dean was dead; the cause was ruled an accidental crystal meth overdose. The homeowner and 911-caller was Edward Buck, a noted Democratic donor and activist. Buck told authorities that he was taking a shower when Dean stopped breathing. He spent 15-minutes trying to resuscitate Dean before calling an ambulance.

Dean was not the first man to die in Ed Buck’s home. In July 2017, 26-year-old Gemmel Moore was found dead in similar circumstances: he was also lying naked on the living room mattress when authorities arrived at the scene. Both Dean and Moore were black men, and Buck is white. Both deaths were originally ruled accidents. While working on this essay in the spring of 2019, Ed Buck did not face charges for these crimes. It was not until a third man overdosed but survived on September 11, 2019, that Buck was charged by the Los Angeles district attorney with three counts of battery causing serious injury (Winton 2019).

When I first heard this story I felt a sting. I was overcome with anxiety over this injustice, and for the next few months, I became obsessed with news surrounding Ed Buck. Who was he? A 64-year-old man who retired to West Hollywood in 1991, Buck has made a name for himself by donating over $116,000 to Democratic candidates and causes—especially those supporting LGBTQA+ and animal rights. Why was he not initially charged for these deaths? Surely, the fact that two men were found dead in his home should signal that something is not legally right. And yet, authorities were apprehensive to investigate.

This case is indicative of a much larger societal issue. Buck is shielded from legal repercussions because of his political connections—his power and privilege stems from his wealth and whiteness. The deaths—-no, the murders—-of Timothy Dean and Gemmel Moore are yet another example of racial violence. Buck fetishizes black men. He hunts them, traps them, and ultimately, he kills them by supplying them with the means to overdose.

Injustices caused by social and racial privilege are an example of a "wicked problem," one that requires an interdisciplinary outlook without an objective solution. First introduced to describe issues concerning policy planning, wicked problems stand in contrast to the "tame" or "benign" problems focused on in the sciences. Their "wicked" nature is defined by several characteristics: (1) they lack definitive formulation, (2) there is no logical end to the issue being addressed, (3) their proposed solutions are not true-or-false but good-or-bad, (4) there is no immediate test of a proposed solution, (5) these problems cannot be studied through trial-and-error, (6) there is no end to the number of possible solutions, (7) all these problems are essentially unique, (8) these problems can be described as symptoms of other problems, (9) the framing of the problem statement affects its resolution, and (10) those who attempt to solve these problems are held liable for their solutions (Rittel and Webber 1973).

How can the humanities add significant value to addressing these wicked problems? As the cases of Timothy Dean and Gemmel Moore unfolded in the public sphere, I was simultaneously engaged in an internal exploration while following an approach outlined by Gregory Ulmer (2003). This work entailed deciphering a wide image emblem derived through pattern recognition across the various institutions that contribute to one’s subject formation—career, family, entertainment, and community. Through this introspective process, I have experienced insights about myself, my scholarship, and my values that lend themselves to a better understanding of these wicked problems—including the those underlying the cases of Timothy Dean and Gemmel Moore.

Divining the Wide Image

In Ulmer’s Internet Invention, he outlines a "hueretic" approach—-one that treats theory as method. The mystorian, the name given to the individual attempting this approach, develops the "wide image" through a series of exercises reflecting on the institutions that have led to the his interpellation, or identity formation (24). Discovering patterns that arise from experiences within these institutions—-career, family, community, and entertainment—-the mystorian cultivates an "image of widescope," or a representation of his metaphysical position, moral beliefs, and mood. Ulmer’s process, which is also a pedagogical method for digital literacy, prepares the mystorian as a consultant whose problem-solving capabilities are attuned to complex concerns inherent to an electrate public (xiii).

Ulmer’s wide image emerges from other humanist methods and theories. It is a practice of divining one’s "personal sacred," a concept described by Michel Leiris as the "objects, places, or occasions [that] awake in me that mixture of fear and attachment, that ambiguous attitude caused by the approach of something simultaneously attractive and dangerous, prestigious and outcast—-that combination of respect, desire, and terror that we take as the psychological sign of the sacred" (Leiris 1988). Identifying which life experiences have contributed to my own personal sacred relies on the mystorian’s recognition of Barthes’ punctum,the poignant sting that occurs when a viewer recognizes a shared signifier between a public archive (the photograph) and his personal memory (Barthes 1980).

In Internet Invention, Ulmer provides a series of exercises for the mystorian to complete in an attempt to divine his wide image. These exercises may involve writing, looking through a photographic archive, or conducting additional research about the mystorian’s community, entertainment interests, or career field. The widesite is the digital, website interpretation of the mystorian’s wide image.

Images

Central to Ulmer’s heuretic is the study of images. While text-based communication remains dominant online, Ulmer refers to images as the primary logic of electracy. Certainly, the modern digital age is characterized by an oversaturation of images. In response, we teach visual literacy as a unique toolset; advocating for a “critical approach” to the interpretation of images that emphasizes their embedded sociocultural significance (Rose 2001). This concept is what Barthes identifies as the studium: images express cultural, linguistic, and political messages through signification (Barthes 1980). The mystorian is not limited to the investigation of photographic images; the approach also encompasses written images—those crafted in a manner akin to the poet, who creates an image with words.

Not all images possess a punctum or, as Barthes described in a prior work, an "obtuse meaning." The obtuse meaning is tied to emotion, what a viewer may recognize as the detail of an image that designates his or her own "personal sacred" and typically triggers a memory from childhood. Again, the identification of the "personal sacred" is key to the widesite’s composition—-looking at images the mystorian seeks the obtuse meaning, or what Ulmer describes as symptomatic of the mood. The mystorian’s default mood, discovered within the elements of the widesite, becomes a powerful problem-solving tool.

Assemblage

The construction of the widesite has much in common with the artistic practice of collage. Surrealist artist Max Ernst described collage as "the systematic exploitation of the fortuitous or engineered encounter of two or more intrinsically incompatible realities on a surface which is manifestly inappropriate for the purpose—-and the spark of poetry which leaps across the gap as these two realities are brought together" (Danchev 2011). The collage is a place of generative, imaginative possibility, derived from a Freudian dream logic and the process of free association. The twentieth century Surrealists, indebted to Freud, defined their art as pure psychic automatism, replicating thought divorced from pure reason (Breton 1924, collected in Danchev 20111). When developing the widesite, the mystorian accepts the project’s Surrealist nature, drawing loose connections between images and allowing patterns to emerge naturally, abstractly, divinely.

To create a digital interpretation of a collage, I employed Kate Compton's Tracery in developing a script that allowed for the random juxtaposition of a collection of personal images identified throughout the development of the widesite. This Tracery collage (Figure 1) is a digital illustration of Surrealist logics. Assembling a collage that may undergo numerous permutations, the three images are drawn together by procedurally-derived chance. The effect is similar to the Surrealist parlor game "The Exquisite Corpse," in which each player draws a separate part of a figure without looking at the parts completed by others. Though the images included in this Tracery collage share a common source—those discovered while completing Ulmer’s exercises—their juxtaposition is derived by chance. It is the possibilities rendered through this chance juxtaposition that is important. For Breton, the cultivation of the imagination represented freedom (1924). Within the digital era, the importance of the imagination is not limited to the artist. It is a "formative power," the antidote to information gluttony that ultimately results in fatigue, our individual and collective "loss of focus, attention, immersion, and connectedness" (Birkerts 2015). It is the generative power of imagination that stimulates passion, discovery, empathy, and scholarship. The widesite is a representation of this stimulus.

Mapping the Popcycle

Age 4, wearing my father's cowboy boots

Through the development of the widesite, I discovered that my wide image emblem is a cowboy/gypsy boot. I arrived at this image after recognizing the repetition of this object and its significance throughout the popcycle, Ulmer’s name for the map linking the institutions of family, community, entertainment, and career.

The emblem first emerged within family. There is a photograph from my childhood where I am wearing my father’s too-large cowboy boots. The image is humorous, and yet it is also an austere reminder that I will never "fill my father's shoes." Physically, these boots still do not fit me. As a rebellious teenager with a fake ID, I would borrow these boots and wear them to gay bars and clubs. I was not trying to reference the fetishization of cowboys within queer culture; rather, I simply liked the extra inch of height these boots gave me. In college, I replaced the boots with stiletto heels. And while the heels were more closely aligned to my gender expression, I always felt more physically and emotionally comfortable wearing my father’s boots.

Jacob Summerlin,

Orlando landowner and philanthropist

The cowboy also emerged within my community history assignment. For the past six years, I have lived in a home on Summerlin Avenue in Downtown Orlando. Summerlin was the surname of a prominent Orlando landowner. A rancher who made his fortune by selling cattle in the years after the Civil War, Jacob Summerlin was known as the "King of the Crackers." He is remembered for donating to the City the land containing present-day Lake Eola. His only stipulation was that the land be properly maintained. In fact, he put reverter clauses in the contract that stipulated the land’s return to his family should the City ever fail to keep Lake Eola beautiful (Florida Humanities Council 2007).

There is an appeal to this myth of a rough-and-tumble cattle rancher as the protector of beauty, though it is not an idea commonly associated with the cowboy. And yet the modern cowboy boot extends beyond its protective purpose, the boots also reflect the wearer’s creativity. The cowboy’s dress boot is often a symbol of identity—-these boots may be custom designed or decorated. It is a fusion of subjective aesthetics and practical function. The boot protects, but it is also beautiful. The fusion of form and function relates to my career duties as a museum curator—-the assemblage of an exhibition is equal parts practical (arrangement logics, budget control, layout accessibility) and beautiful (the design of an aesthetically pleasing, captivating spectacle).

The cowboy boot emerged through various exercises, sometimes in a literal way, but often through abstraction. For example, while completing one exercise that called for the mapping of personally significant locations, I realized that the outline connecting these points on the map resembled the shape of a cowboy boot’s heel.

Quasimodo,

blessing the union of Phoebus and Esmerelda

The connection was less apparent within assignments for entertainment. The movie from childhood that I feel the most connected to is Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Quasimodo exists as an agender character, as he is depicted as a creature occupying the liminal space between man (represented by Phoebus) and woman (represented by Esmerelda). He plays a dual role throughout the film-—he is both the rescued, seeking help to escape his confinement in the cathedral, and the rescuer, helping Esmerelda and the Romani escape Frolo’s treachery. Looking back, I empathize with Quasimodo’s shame—there were many points where I felt like a monster because of my queerness. When I was boy, I remember playing as Esmerelda; dressed in my grandmother’s oversized purple, paisley shirt. I pretended to be Esmerelda as I read my younger sister’s palm.

An insight derived from this family memory supports my existence between what I reflexively entitle a "gypsy"/cowboy binary. I recognize that this statement is problematic because I am relying on stereotypes associated with these identities: the "gypsy" appropriation on which American depictions such as Esmerelda rely is pejorative and reductive. My intention is not to validate these stereotypes, but to reflect on the cultural mood evoked through the (mis)representation of these identities, and to explore the gendered framework that these pejoratives evoke:

Gypsy: woman, playful, fortune teller, law breaker, purple, flowing silk

Cowboy: man, austere, fortune-driven, lawmaker, yellow, bootcut denim

It is in between these two characterizations that I identify. This relationship was further developed through the exercise or comparing the moods of a song’s lyrics and music. I chose to look at Fleetwood Mac's "Gypsy." Watching the original music video, I realized that Stevie Nicks wears cowboy boots with her flowing white dress—-a blending of cultural symbols. Nicks is both feminine gypsy (dress) and masculine cowboy (boots), and this creative character/gender construction encapsulates the mood of my wide image. The boot may be worn by a cowboy or a gypsy—-the wearer of my wide image’s boot is fluid.

With this reflection in mind, the cowboy/gypsy boot becomes a guiding emblem/representation of my metaphysical outlook and connected values. The boot functions as a form of protection, shielding its wearer from the treacherous landscape. And while I see protection as a core theme within my role as an educator (protector of knowledge) and curator (protector of objects), the cowboy boot elicits a specific defense: self-protection. Protecting myself through a regimen of self-care has become increasingly important in adulthood. I have had to make conscientious efforts to address my mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing. The cowboy boot serves as a symbolic reminder of this effort as I progress in both my professional career and scholarship.

Further, at the heart of my career is community engagement. While the cowboy is often portrayed as a stoic loner, the gypsy’s survival is dependent upon the strength of her community. As a museum educator, I design programs with community in mind. I seek ways of opening the Museum to traditionally overlooked audiences like visitors with visual impairments, adults with learning or developmental disabilities, or youth experiencing homelessness. I believe that in order to build a better, stronger community we must first critique our current institutional practices and develop a compassionate response. The cowboy/gypsy boot embodies power-—power that must be harnessed in order to address the challenges within the community.

Consultation

Having identified the emblem at the heart of my wide image—-the cowboy/gypsy boot—I have returned to face the case of Gemmel Moore and Timothy Dean and the broader, wicked problem this represents. Proceeding methodically, carefully—the way of the cowboy as he treads through dangerous territory—-I start by trying to understand what aspects of this specific case caused my initial sting. Throughout the course of this project, there were many cases where power and privilege have impeded justice—-for example, new evidence was discovered that reinforced the Sackler family’s role in causing the opioid epidemic-—and yet none of these cases captivated me. I have come to accept that my interest in Buck’s case derives from an ability to identify with both the victims and the perpetrator.

Timothy Dean and Gemmel Moore. In the weeks following their deaths, the media assessed Moore and Dean as wayward. Moore was repeatedly identified as a prostitute. In one video, his mother corrected the interviewer—-"Actually, he preferred to be called an escort."”" Dean, who was twice Moore’s age, held a day job as a fashion consultant at Saks Fifth Avenue, but he moonlighted as an adult film star. Both Moore and Dean had a history of drug use. These characterizations beg the question: were Dean and Moore blameless victims? After all, they willingly arrived at Ed Buck’s apartment—-a final stop on a wayward journey.

A friend of Dean’s said, "He wasn’t an angel, he wasn’t a devil. He was in between, like everyone else" (Hamilton 2019). This quote sticks with me. Dean and Moore embody the gypsy stereotype. They are the wanderers, the traveling misfits. Neither entirely good nor bad, but existing in between.

I have compassion for Dean and Moore, but I cannot fully understand the life circumstances that brought them to Buck’s door. I grew up with privilege—my race, education, and economic status have earned me undue power throughout my lifetime. I am currently the same age as Moore when he died, and yet our circumstances seem radically different. I cannot fathom a life where I lose autonomy over my own body in order to survive. And while I try to remain compassionate, there is a sad part of me that judges him for being an escort. Is this the fate of the gypsy? Is the cowboy’s role to protect the ill-fated gypsy? To prevent her death? These questions burn in me as I continue to research the case.

Ed Buck. Again, it is difficult for me to admit this, but I am able to identify more with Buck than with Dean and Moore. We share privilege—we are both white, male, educated, and economically secure. We also share passions—Buck is an outspoken, liberal activist who fights for LGBT rights and I support similar views. Gemmel Moore’s journal damns Buck as the one who led him to drug addiction (Cannick 2018). I hate him for this. It reminds me of those friends who once convinced me to start smoking cigarettes. And yet, what about the hundreds of people I have likely pressured into smoking over the years? Am I culpable? Am I Buck?

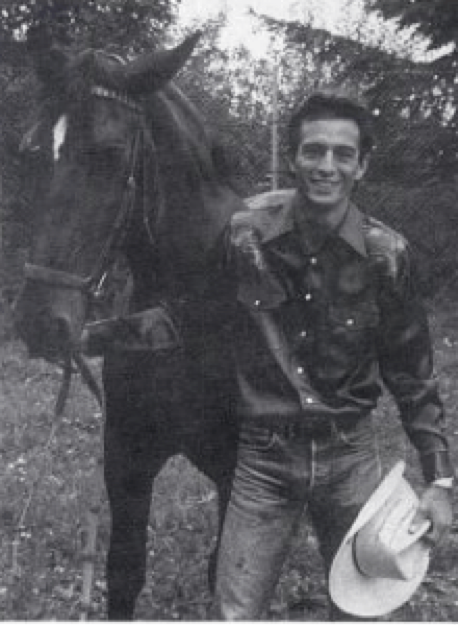

Ed Buck,

photographed in 1989 at

Arizona International Gay Rodeo

It’s the photograph that confirms the connection. Accompanying a news profile of Buck is an image from Arizona’s 1989 International Gay Rodeo (Figure 3). Buck was named the Grand Marshal of the event. He is much younger in this image. Lean. Good looking. I am attracted to this man. Buck, quite literally, embodies the cowboy. He is the protector, the path forger. Buck’s friend described him as someone who helps others, “They’ve been homeless; he’s helped them get a job…he’s helped them get out of drugs. When they have nobody else to turn to, they turn to him" (Branson-Potts, Winton, & Hamilton 2019).

However, his outreach into the homeless community was often predatory. In the wake of these deaths, other men have come forward stating that Buck pressured them to use drugs when they stayed with him. He lures them to his home under the guise of the cowboy, but his intentions are not honorable. He is protector and predator. After all, a bandit may also wear cowboy boots.

The disjointedness of Buck’s character is typical of the cowboy as American myth. In his analysis of Classic Hollywood cinema, Robert Ray describes the cowboy as blurring the line between "official hero" and "outlaw hero" (Ray 1985). While the outlaw hero represents "self-determination and freedom from entanglements” the official hero stands for "the American belief in collective action, and the objective legal process" (Ray 59) Within American mythology, the outlaw hero is often a reluctant hero: he begrudgingly relinquishes his self-serving nature to protect the community through a redeeming act. The cowboy is the culmination of these competing values—-a complexity that is transferable to Buck.

Even with this rationale, another question resounds: why? Why did Buck lead these men to their deaths? Though I am limited in my understanding of predatory behavior, my visceral reaction to this question prompts an answer, though certainly not a justification: loneliness. Waywardness to the gypsy is loneliness to the cowboy. Thirty years have passed since Buck was the Grand Marshall. In recent photographs, he looks withered, emaciated, tired, old. I imagine the vanity that permeates West Hollywood’s gay community. I imagine Buck becoming increasingly invisible within this community: the craving for attention; the stoic cowboy dreams, wishes, hopes. The cowboy seizes the reigns of his loneliness, directing the steed to charge forward, unapologetic for those he may stampede along the way.

Waywardness, loneliness. The vices of the gypsy and cowboy are just as important as their virtues. Though unique, these vices are connected. The perception of waywardness is perhaps what attracts the cowboy. Motivated by his loneliness, the cowboy seeks out the wayward gypsy. He may act as protector, a reluctant hero who saves the gypsy from becoming lost. Or, as Buck demonstrates, he may lash out as predator. Like a Venus flytrap, he lures the gypsy to his lonely lifestyle, trapping her—-the doomed promise of the wayward fulfilled. This choice between protector or predator hinges on compassion.

Is there a resolution? Shouldn’t a consultation end in action? As is the case with many humanistic inquiries, the divining of the wide image is a method for better understanding our condition and interpreting the record; it does not provide a direct, clear solution. In this case, justice, what the cowboy is meant to stand up for, is elusive. Though Buck was later arrested following his involvement in a third victim’s overdose, true justice will not occur until we dismantle the system of power and privilege surrounding this case. It is a calling that requires both the gypsy and the cowboy-—they do not exist as separate beings, but rather as one. The cowboy/gypsy boot guides my thinking, my actions, my teaching. It is through these practices that I challenge normative power structures. It is with the lure of the cunning gypsy that I attract others. It is with the determination of the assertive cowboy that I demand change. The application that follows demonstrates the emblem of the gypsy/cowboy boot’s effect—-providing closure to this particular endeavor, yet an opening to future inquiries.

Application

Museums operate as discursive spaces: community meeting places for diverse audiences of all ages, backgrounds, and abilities. Within the latter part of the twentieth century, museum education emerged as a professional field that prioritizes the experience of the visitor over the curation, collection, and preservation of artifacts. The "participatory museum," an idea championed and explored by Nina Simon, presents opportunities for visitors to creatively engage in the curatorial process and construct their own understanding of the objects/exhibitions on view (2010). Though Simon advocates for self-guided experiences, museum educators, like me, are trained arbiters navigating visitors through their experience. Within art museums, educators assist the visitors by guiding them through discussion to their interpretation of the works on view. Within this dialogue visitors build connections through sharing of past experiences, memories, and knowledge.

The recognition of the cowboy/gypsy boot as my wide image emblem has affected my professional work as a museum educator. In the months following my completion of the widesite, I began working on the development of a new program model intended to engage high school-aged LGBTQ youth involved in their school’s Gay-Straight Alliance, an extracurricular peer support group that facilitates a dialogue regarding issues surrounding queerness. The program—-Project Qurator-—is intended to introduce students to the relevance of identity to artistic practice, and then train them to design and curate their own digital exhibitions of queer contemporary art using Google Sketchup. There are several learning objectives to this program, but perhaps the most important is the cultivation of empathy through the recognition of shared struggles, solutions, and paths forward with the artists studied.

In my original plan for this program, student sessions were to be facilitated by a trained docent who was familiar with the works in our institution’s collection. It was at this point in the planning that I recalled the wide image and the lessons it represents. While I have worked with LGBTQ youth identified as at-risk for several years, I have never explicitly framed this population in the mindset of the gypsy. Of course, Project Qurator is meant to foster a sense of direction and understanding for those students who may not feel a sense of belonging within a traditional academic setting, thereby seeking out extracurricular opportunities to build a network of peer support. Gay-Straight Alliances, and by extension Project Qurator, offersdirection to those we may consider wayward. Yet, there seemed to be an aspect missing in this program model-—the element of the cowboy.

Reflecting on this absence, I was reminded of Buck. I began to think of the loneliness of the cowboy. Within my community service work I have met many older men and women who have expressed a sense of loneliness, a feeling of disconnect from their community that is exacerbated with age. Especially amongst older LGBTQ adults—-oftentimes trailblazers who forged pathways for the gay rights movement-—I have observed a lack of connection with younger generations. If we are to consider this group representative of the cowboy, and the students representative of the gypsy, how then might these two groups both strengthen, like the leather of the boot, through thoughtful programming?

Rather than utilize a current docent, I have decided to recruit and train older LGBTQ adults as Project Qurator facilitators. Again, the program’s intention is empathetic understanding, but now the focus is placed less upon the lessons provided by named artists, and more on the intergenerational dialogue between actual people. The objects and their makers become the vehicle for building community, rather than the primary focus of study. It is these types of interactions that museum education should aspire to. It is the direction of the cowboy and the needs of the gypsy that inspired my understanding and planning. The intention of Project Qurator will hinge on compassion—-guiding the cowboy to the role of hero rather than predator. It is the opposite of the relationships Buck cultivated with younger gay men-—it is nurturing.

This project is one application of the wide image to my career output, but the values and philosophies encapsulated by this emblem continue to affect my actions in many spheres. Ulmer’s heuretic fosters a humanist mindset attuned to the affordances and limitations of an era defined by hypermedia. By tracing this pattern through the archive of memories, images, and ideas that have shaped my understanding of the world, I am armed with the emblem of the cowboy/gypsy boot as a guiding force to inspire and create change.

Works Cited

Barthes, R. (1980). Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang.

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

Birkerts, S. (2015). Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Graywolf Press.

Branson-Potts, Hailey, Richard Winton, Matt Hamilton, (2019). “Who is Ed Buck? The Erratic Life of the Democratic Donor in Whose Home Two Dead Men Have Been Found.” Los Angelos Times, January 18, 2019.

Cannick, J. (2017). "#BREAKING: Journal Documents How Wealthy Democratic Donor Hooked Young Black Gay Man on Meth Before His Death | Jasmyne Cannick." I am Jasmine, August 14, 2017. https://iamjasmyne.com/breaking-journal-documents-how-wealthy-democratic-donor-hooked-young-black-gay-man-on-meth-before-his-death/.

Danchev, A, ed. (2011). "Manifesto of Surrealism" (1924)." In 100 artists’ manifestos: from the Futurists to the Stuckists (pp. 241–250). London: Penguin Books.

Danchev, A. (Ed.). (2011). 100 artists’ manifestos: from the Futurists to the Stuckists. London: Penguin Books.

Florida Humanities Council. (2007). "Jacob Summerlin: The Cowman Who Was King of Crackers." Retrieved from Tampa Bay Newspapers

Haag, M. (2019, January 11). "Ed Buck, Political Activist, Faces Questions Over 2nd Dead Man in His Home in 2 Years." The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/us/ed-buck-gemmel-moore-hollywood.html

Ray, R. B. (1985). A Certain Tendency of the Hollywood cinema, 1930-1980. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). "Dilemmas in A General Theory of Planning." Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Rose, G. (2001). Visual Methodologies. London: Sage Publications.

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Mseum. Santa Cruz, California: Museum 2.0.

Ulmer, G.L. (2003). Internet Invention: From Literacy to Electracy. New York: Longman.